Confronting Concussions

Discovering the underlying dangers of sports and the brain

Bellwood-Antis athletic trainer Jesse Glass running concussion protocol on an athlete.

January 15, 2020

According to CDC estimates, anywhere from 1.6 to 3.8 million sports and recreation related concussions occur each year in the U.S., and ten percent of all contact sport athletes sustain concussions yearly.

Brain injuries cause more deaths than any other sports injury, accounting for 65 to 95 percent of all football fatalities alone.

As a result, high schools have been forced to reassess how they deal with sports-related concussions, changing everything from preventative care to concussion protocol.

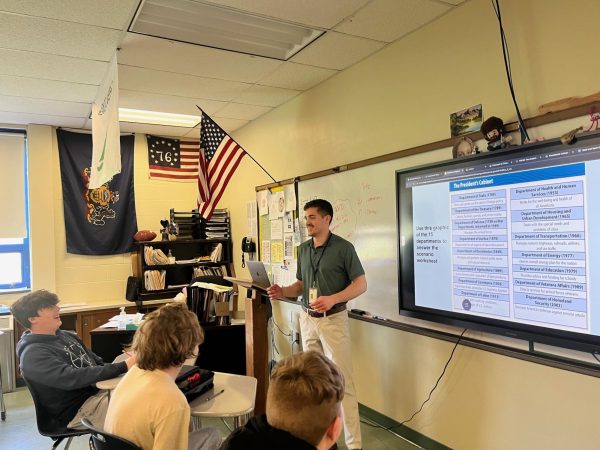

Mr. Matthew Elder, a teacher and soccer coach at Bellwood-Antis, has seen a change from when he played in the early 2000s to now.

Soccer is one of the leading sports for head injuries

“When I played soccer in 2006, concussions were a thing, but it wasn’t something stressed or checked by impact tests,” he said. “As a player I was more concerned about my ankles than my head. There were definitely times I should have been checked: elbow to the head, improper header form, kicked in the head. I insisted I was fine since I was competing for a starting spot.”

The shift Mr. Elder refers to has taken place across the country, including Bellwood-Antis, as medical professionals learn more about the damage done by sports-related hits, not only the explosive kind, but the repetitive hits delivered day after day in practice.

“Even one of the largest youth organizations around has banned heading the ball for ages 12 and under,” said Coach Elder.

TERMS

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury—or TBI—caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. The sudden movement can cause the brain to bounce or twist inside of the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain or even permanently damaging brain cells.

All concussions are serious. According to UPMC Sports Medicine, any level of a concussion can be a serious medical issue that requires prompt care. To avoid repeat injury, it’s crucial to manage concussions until complete recovery

B-A football coach Nick Lovrich said his team had fewer than 10 concussions this season, which is actually a little lower than years past. Still, it’s quite a scary statistic, considering 5 of 10 concussions go unreported or undetected.

But football isn’t the only culprit. Girls’ soccer sees the second-most concussions of all high school sports. Girls’ basketball sees the third most.

Coach Lovrich and his daughter Alexis did a study on B-A athletes from 2014 to the fall of 2017 as part of a middle school science project. The study examined 450 total athletes across all sports at Bellwood-Antis and of that 450, 76 athletes were diagnosed with concussions. Of those that sustained a concussion, 27.36% received more than one, meaning that at a small Class AA school like B-A, there was a total of 140 concussions across 76 athletes.

As a result of numbers like those, which are common, schools have taken a proactive approach to prevent head injuries and concussions. In soccer that means emphasizing the basics.

“Everything starts with proper form and training. In practice, we stress how to head the ball, defending, situational awareness, proper tackling, and other forms of training. We do this so players can avoid putting themselves in concussion-possible situations,” said Coach Elder. “Playing under control and with game awareness can’t eliminate them, but can reduce the possibility of concussions.”

Football coach Nick Lovrich is a big proponent of safer play.

Coach Lovrich referred to changes in the way the football team coaches.

“We have implemented more of the hawk tackling or shoulder tackling principles, which have been shown to lessen hits to the head,” he said. “We emphasize at practice and games using the proper technique and keeping your head up when hitting. We will even talk about technique during film sessions to reinforce the drills we do in practice.”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE MADNESS

Rads/s^2 is radian per second squared. This is the unit of angular rotational acceleration magnitude. In football games the average force on players was 1947.5 rad/s^2 and at practice it was not much lower at 1817.5 rad/s^2. That means in games players are sustaining an average of 18,597 rpm of rotational acceleration. Players were also sustaining linear hits or the north south hits.

According to GSU’s HyperPhysics Project, a 160 lb person—wearing a seat belt and traveling at only 30 miles per hour—experiences around 30 G’s of force in a front-end collision with a fixed object. That’s 2.4 tons of force acting on the body. What’s worse is that if the vehicle occupant was not wearing a seat belt at the time of the crash, they would likely experience 150 G’s, or 12 tons of force.

Jump to college football. On average every time a collegiate football player is hit in a linear motion they were undergoing 31.52g’s of force. It is like being in a 30 mph car crash every time. That is just the average of all hits, so when you take into account the “highlight real” big hits, there is no telling how much force is being enacted upon some players, not to mention all the other factors of a player, size, speed, and weight.

HITS OVER TIME

The problem is, preventing all concussions is impossible, especially in contact sports where daily hits are a routine part of the game.

Coach Elder says it is hard to put a number on how many hits soccer players are taking per week.

Honestly the incidents that worry me as a coach most are the freak ones

— Mathew Elder

“Honestly the incidents that worry me as a coach most are the freak ones such as a wayward shot, a player catching an elbow to the head, or a goalie so zoned in and focused on the play that they dive into the goal post,” said Coach Elder.

It’s hard to deny the danger of football, where every practice can result in hits dangerous to the head. Considering the sheer amount of hits football players take in a season, it is no surprise that football is the leading sport for concussions. A study done in 2010 done by the National Athletic Trainer Association total found that in a single college football season, the number of impacts players received was very high. The maximum number of head impacts for a single player on each team was an average 1,292 throughout the course of a season. Impacts per practice was an average of 14.3 and slightly higher in games at 16.2. Linemen and linebackers had the largest number of impacts per practice and per game.

And if a player sustains 1,000-plus hits in a collegiate season, what about the other hits to the body or impact from falls? These are major contributors to the research, because you don’t have to always hit your head to receive a TBI. Body hits or hits that result in falling on the ground could apply enough force to cause a concussion either on minor or major scales.

“It is no different to someone who has an ankle injury or a shoulder injury,” said B-A trainer Jesse Glass. “If you don’t have that fully healed you will continue to damage yourself more throughout practice and games. The brain is the same thing; it is an organ and if you continue to cause trauma to it day after day, even though you have a break between seasons, if you go back and practice again and cause more trauma you are going to see the effects. I think we are going to see the effects more and more as the game progresses. Athletes are bigger, stronger, and faster now. We will absolutely see the effects.”

As a result, hitting at practice isn’t as constant and physical as it once was.

CHANGES IN METHODS

Coach Lovrich speaks frequently on how he and his staff have implemented safer ways of playing the game and tackling and provides a parallel to the past when he first started coaching in 1997 to now.

A huge part in creating change has been the world accepting that concussions are a health threat and reacting to the information that is coming out with action. With new information being provided by major sources such as the CDC, the Mayo Clinic, and Johns Hopkins, the world of sports has made droves of changes.

“Coaching education has also changed,” said Coach Lovrich. “The PIAA mandates that every coach in PA needs to take a concussion safety course to help with prevention and recognizing symptoms. Our trainer does a great job recognizing when an athlete may have a concussion and following the five-step process that is mandatory to return to play. We even have doctors who specialize in concussion care in our area that he works with to help our athletes. It used to be that an athlete got his or her bell rung and would just shake it off and return when they felt okay. Now there are steps that an injured athlete needs to do before returning to play.”

Trainer Glass has experienced the shift as well throughout his career, which has spanned nearly decades.

“This is my 15th year of athletic training, and over time the thing that I have seen most is treatment and how we deal with concussions,” he said. “Before we had just three grades of concussions and we don’t do that anymore. We go by symptoms, the amount of symptoms, the total amount of symptoms, and we monitor them daily until (the athlete is) symptom-free. Before there was a time period, we would have three to five days until you could return, and even if you had symptoms you were allowed to return. Now it’s a week or two weeks symptom-free until you can return to play.”

A POLICY OF CONTAINMENT

Unfortunately there is no way to stop brain injuries from happening inside or outside of sports. All concussions are different and they occur across the boards. In 2019, an estimated 155,650 children sought care in U.S. emergency departments for a recreation-related traumatic brain injury, according to a new MMWR Report by the CDC.

Coach Lovrich said he is trying his hardest to protect his players, but there is no for sure way to prevent them all.

“You have 22 bodies moving around at one time and you cannot control what everyone does on each play, but we are working very hard to prevent them from happening,” said coach Lovrich.

it is a contact sport, so you aren’t really going to be able to change anything to make it safer

— Jesse Glass

Trainer Glass concurred, saying even improvements in technology, like better helmets, don’t offer the hope of preventing brain injuries in a sport like football.

“It is what it is. It is a contact sport, so you aren’t really going to be able to change anything to make it safer,” he said. “That is the risk you take when you decide to play sports like football. You can design any helmet on the Earth and it isn’t going to reduce the risk of concussions. The brain shifts inside the skull when you get hit and that’s just the way concussions occur. in my opinion, there is no way to make it safer, per say, to decrease head injuries.”

A study was done and published as recently as September 14, 2019 titled Routine Hits In a Single Football Season May Harm Players’ Brains. Adnan Hirad at the University of Rochester in New York led the new study. It looked for signs of brain changes due to head impacts. Hirad’s team recruited college players to participate in the study during the 2011, 2012 and 2013 football seasons. Each player wore an accelerometer, which allowed the team to monitor intensity and direction of the hits during the whole season. Thirty-eight players participated and together they sustained 19,128 hits to the head, with 59% sustained in practice and 37% in competition.

Each player went through pre and post brain scans. Reserchers found by the end of one season of play, the players’ fractional anisotropy scores had dropped, on average, in their right midbrains. Fractional anisotropy is a gauge of the connectivity of white-matter fibers in the brain. How big the drop was tended to be linked more to the number of hits that rotated a player’s head rather than to the number of direct head-on hits. Those rotational forces might be especially damaging to brain tissue.

White matter is the tissue that allows the brain to transmit signals, allowing for brain functioning and learning.

“People have less intuition in rotational forces and the dangers associated with those forces in comparison to linear forces,” said Dr. Alice Flarend, a physics teacher at Bellwood-Antis.

FACE THE FACTS

From major research on football players at the collegiate level it is clear that your average routine hit that can jar the body and jerk the neck can cause a decrease in white matter deep in the brain. Thousands of CDC reports have come out and a slew of case studies surrounding concussions have brought exposure to the real hard statistics.

The effects of constant hitting is a huge concern that we need to focus on

— AD: Charlie Burch

“That is the risk you take when you decide to play sports like football. You can design any helmet on the Earth and it isn’t going to to reduce the risk of concussions. The brain shifts inside the skull when you get hit and that’s just the way concussions occur,” said Jesse Glass.

The baseline of our personalities, the ability to love and learn, the actions we make simple, from breathing all the way to performing incredible feats of strength and creativity – it all boils down to a little three pound organ protected by a 6.5 millimeters skull.

It is our life blood held up by a tiny stem in a small cocoon and athletes need to protect it. You only get one brain, and the effects from damaging it are exponential. At the same time, athletes will always want to push the boundaries of their physical abilities, and with concussions being an injury that is nearly impossible to prevent, schools like B-A may always be playing a game of catch-up.

“The effects of constant hitting is a huge concern that we need to focus on. We can’t change the past, but we can change the future and help minimize the effects on the brain,” said athletic director Mr. Charlie Burch.